Good people make bad people uncomfortable

And bad people are boring

[This photo is from a UNICEF Instagram ad, asking for money. This post is not a serious attempt to advance an argument based on evidence and logic, but it’s not a sermon either, because it’s as cynical as my usual #content, and because I’m not a believer.

It’s about being good, but it’s open about there being no sure upside to practising virtue. I just muse on my own experiences on the assumption that you would like to be a better person anyway—even if you don’t trust my judgement and won’t act on your ambition.]

If you follow me on Twitter, you might know that someone who was a client of mine for the better part of a decade—the sort of client who would come to sit with me in my office for in-person consultations—was recently convicted of attempted murder and jailed for life1. Despite the would-be victim of the attempted murder being seriously injured in the failed attack, no one I have told the story to has expressed more interest in the victim than in the perpetrator.

They assume that a man who conspired to kill another man has some hidden depths. But interesting villains are like submarine-on-submarine underwater battles: almost all figments of the imaginations of writers. And writers give their antagonists deep motivations and elaborate plans, because character development, personal goals, and complex structures make stories. Yet most individual acts of evil are tantrums: childish, narcissistic, a surrender to dumb urges—not willed steps to a new order driven by Dark Secrets. In the UK, real-world killings by individuals don’t resemble country-house murder mysteries. Usually, when not gang-related, they’re so-called “crimes of passion”, and the police don’t have to decipher cryptic clues; they arrive at the scene to find the perpetrator kneeling over the bloody body, sobbing, with the weapon their hand.

My experience hasn’t changed my view that bad people are boring. Most of them are like you or me, but with less impulse control, or like you or me, but with less empathy for others, or like you or me, but with their moral boundaries eroded or broken. When I use the phrase “like your or me”, it’s not to diminish the importance of the moral difference, but to counter the trope of the Bad Guy as unusually clever or subtle or cultured or witty. Most thugs are thugs.

In peaceful countries like this one, with at least basic respect for rule-of-law, and plenty of more-or-less law-abiding fellow citizens, being bad can be a winning strategy. That is, given a sufficient large number/fraction of non-defectors, cheats do, in fact, prosper: If you give into your base instincts in such a society, then a large enough population of not-evil people—suckers—may let you get away with it, and you may gain from their compliance with the law/their default trust in your good behaviour.

So, by definition, in law-abiding societies, being not-evil is common, but its costs are often shared. Everyone who pays taxes pays for the benefits fraud; only the good samaritan pays when he stops to help a car-jacker pretending to have broken down. Being genuinely good is rare and unrewarding at the best of times; when it’s costly, its costs are mostly borne alone.

So I have never been interested in true crime books or shows, I am always less interested in gossip about local criminals than my peers, and, once I know someone is a bad person, any attraction I might have for them evaporates.

In contrast, I have always been fascinated by genuinely good people. I’m not fascinated like a priest; I’m fascinated as a cynic—because I don’t see the payoff.

What is a genuinely good person?

Have you ever met a good person? I don’t mean a nice person, a polite person; I don’t mean a warm or charismatic or sympathetic or charming person. I mean a person who makes the world around them better and, even when they aren’t currently making the world a better place, they’re trying to make the world a better place.

A good person makes an independent effort to work out how to be good in any given situation.

A good person is willing to pay a personal toll in order to help others.

A good person is not only good when no one is looking—a good person is good when no one will ever know.

A good person tells you what you need to hear, not what you want to hear.

Years ago, I worked at a research institute that probably had one or two hundred employees and graduate students. There was one relatively junior member of staff there who was both a charismatic person and a good person. Both of these qualities made them well known outside their own department (which was not my department). But their goodness caused more discomfort to others than their charisma.

Genuinely good people don’t virtue-signal

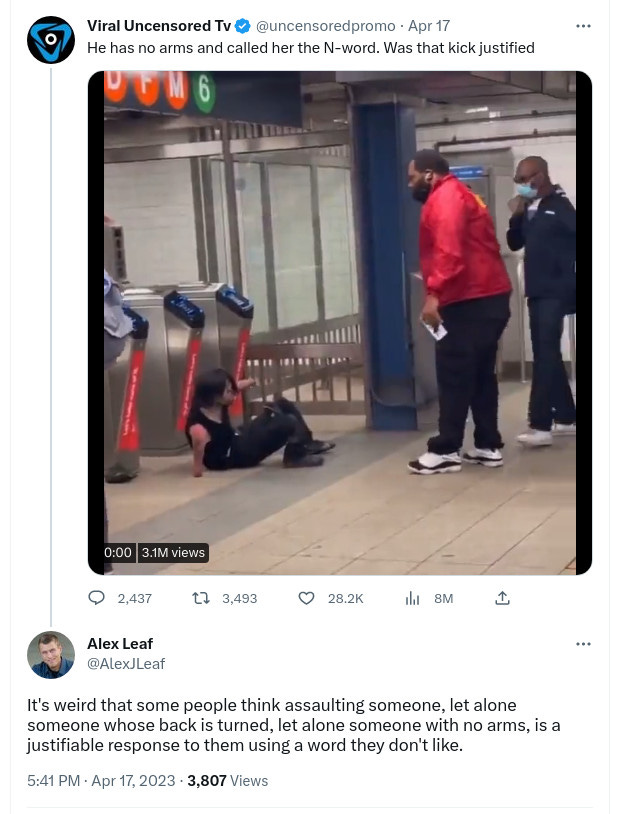

Overuse can blind us to how insightful the phrase “virtue-signalling” can be. So much of contemporary morality elevates appearance over substance. An example from this week: thousands of Twitter users seem to believe that the use of the word “nigger” justifies kicking a man with no arms to the ground.

https://twitter.com/AlexJLeaf/status/1648003821636026369

And virtue-signalling scales up the global level, where, also this week, Germany closed its last nuclear plants to appease its powerful “green” political bloc, resulting in the country consuming more of the fossil fuels the burning of which that same bloc claims are responsible for irreversibly damaging the Earth’s climate.

How good people cause bad people discomfort

By setting a good example

A good person will try to do the right thing, regardless of what their peers consider to be acceptable. This is a double challenge to Counsell’s Second Law:

“The two most powerful forces known to contemporary humankind are peer pressure and the desire for a quiet life”

The most devastating outcome of the arrival of a good person with sufficient charisma is that they establish more demanding moral norms for those around them. So everyone has to a) change and b) change in a way that costs.

By calling out bad behaviour

“Bad men need nothing more to compass their ends, than that good men should look on and do nothing.”

In an affluent, safe milieu, being passively good is easy. The real measure of a person is whether or not they’re prepared to object to, or even obstruct, wrongdoing.

Is there a lesson here?

Whatever the likes of Just Stop Oil, the Socialist Workers Party, Mermaids, or the Palestinian Solidarity Campaign might tell us, we do not presently live in a nation subject to a Great Moral Test; we are not collectively bloody-handed at the inception of a genocide; Donald Trump is not going to buy the NHS; the government is not run by Nazis-in-disguise. Even on an individual level, most of us are no more or less than passively good. The genuinely good are not having to wrestle with the question of whether or not they should assassinate Rishi Sunak before he gasses all the trans kids. What does any of this have to do with us?

We don’t have to live in bad times to learn from good people. The good people I’ve known have taught me a few valuable, if not exactly uplifting, lessons, whether I have wanted to learn them or not:

I want to say that being good is guaranteed to pay off over all on this earth, but I don’t believe that it does. I do believe that goodness can pay off after a long time and sometimes pay off big—I have seen good people fall in love with other good people for example—and I do believe that many merely-not-evil people reciprocate goodness, just as many do not.

So, if you want to be good yourself—rather than just doing-unto-others-as-they-do-unto-you, which game theorists believe has a positive return as a rule-for-living—you have to either believe in a reward after life or want to do it for its own sake.

Genuinely good people tend not to be mugs, because genuine goodness is not about virtue signalling. The kind of tough-mindedness needed to distinguish between the appearance of doing good and the substance of being good is the kind of tough-mindedness that spots roaring lions among the sheep (and recognizes other shepherds).

So good people can help you to spot bad people—even passively, because bad people tend to take an immediate dislike to good people, who represent a threat to bad people in a way that merely-not-evil people do not.

Lastly, and relatedly, good people test our own ability to distinguish between those people who makes us feel better and those people who make us better. If you’re lucky, you get to meet people who lift your spirits as well as force you to up your game; but even when the same person is capable of having both effects on you, you rarely get to experience them simultaneously.

I never believed him to be an angel, but it took a long time for the true character of my ex-client to reveal itself to me. One tiny piece of advice I want to give you, inspired by his terrible story—advice that’s relevant, but also has as little to do with him as possible—is that it can also take a long time for the true character of good people to reveal itself too. So maybe you should stick around through the part where they make you feel bad about yourself.

Actually 35 years, with no release possible within the first two-thirds of the sentence.

Only a matter of time before your least favourite people discover this blog post and invoke Jeremy Corbyn as an example of a person whose goodness made him unpopular...

Enjoyed this. Relatedly, a common observation about art/storytelling that I sharply disagree with is "good people are boring" (or make for boring stories). I find the most memorable characters are invariably those who are at least trying to be good, even if they have to wrestle with the costs that comes with (for themselves and others), or requires employing dubious methods.

I wish we talked about good people more often. I will try.