Just A Bite

Sampling Apple TV+

Click below to hear me read this post:

To do my bit to save it from bankruptcy, I take out two months’ subscription to Apple TV+ and review three of its most prominent original productions (but not Severance).

The Gorge

It’s rare that a high concept is tempting enough to make me hand over cash for the film built on it. But I caught the trailer for The Gorge and, even though I could see it was a cynical attempt at a Gen-Z Valentine’s Day date-flick—bit of army and horror action for the lads, bit of edgy romance for the lasses, precision-engineered by the market research department at Apple—it made me want to stream it, for the simple reason that it looked entertaining1 and I wanted to be entertained.

Dear reader, I took out a month’s subscription to Apple TV+ and I watched The Gorge and I was entertained.

Don’t get me wrong; The Gorge is rubbish. But there’s Bad Rubbish: every book in the Da Vinci Code series. There’s Good Rubbish: The Empire Strikes Back. And there’s Not-Bad Rubbish, like this. It was also not Annoying Rubbish: There were no “progressive” homilies; there were no artistic pretensions; there was no Mark Rylance.

As with Alec Guinness in the aforementioned Good Rubbish of the original Star Wars trilogy, Sigourney Weaver is roped in, at no-doubt huge expense, to provide actorly heft and cross-generational name recognition. But the leads—Miles Teller and Anya Taylor-Joy—are both capable performers, albeit playing this videogame on Easy Mode, and a handful of non-extras give them solid support.

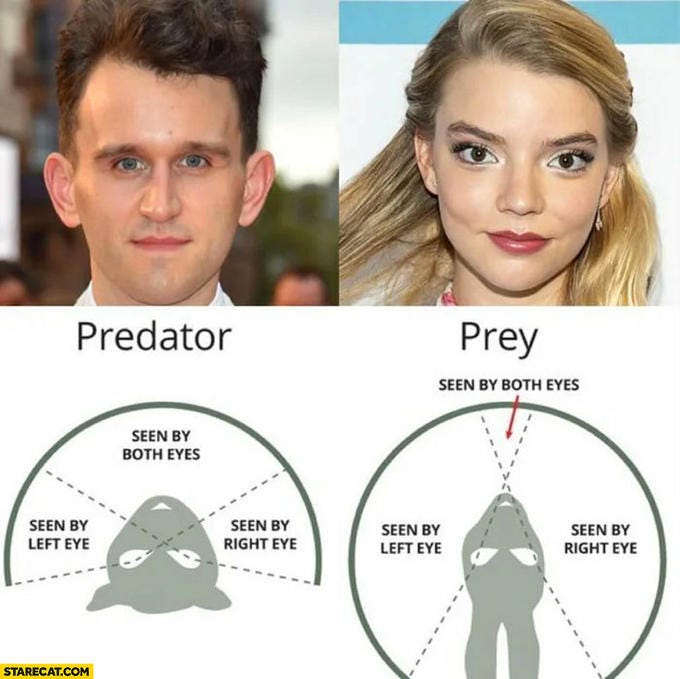

Teller and Taylor-Joy are also “unconventionally good-looking”. In the everyday world, this is a euphemism for “bordering on ugly”; but, in Hollywood, this means that, on any random weekday evening in any random provincial nightclub, they’d be the fittest couple present. He’s giving Ripped Nerd and she has that fashion-model Sexy Space Alien thing going on.

Which reminds me that the casting of two of the principals in The Queen’s Gambit, the streaming show (a Netflix original) that secured ATJ’s place in the mainstream, gave us some glorious memes.

The trailer for The Gorge doesn’t mislead us about its plot either: Hot, tormented western assassin (Teller) and hot, tormented eastern assassin (Taylor-Joy) are assigned to opposite sides of the eponymous gorge, a deep, tree-shrouded scar on the landscape of an unknown far-off country, a scar that hides a dark-and-deadly Cold-War secret. Each killer is ordered to keep that secret in its place without being told exactly what the secret is. They are also each ordered by their superiors not to fraternise with the respective appointed agent of the old enemy on its other side.

Like all good high concepts, it’s a What-If? on the part of its writers that immediately provokes questions on the part of its watchers: “What is the dark-and-deadly secret?”, “What’s going to happen when the two killers, inevitably, start fraternising with each other?”, “Will either or both of them die when they, inevitably, come face-to-face with the dark-and-deadly secret?”

The answers to these questions were, inevitably, preposterous; but I didn’t care, because the action is brisk, the actors are easy-on-the-eye (even if their chemistry is less than convincing), the effects are good enough to get the job done—the budget went on the big-name cast—and the whole freak show has no fancy airs at all. Everyone craves a dirty burger in their viewing diet from time to time; but, even in our age of content bounty, well-made, if overcooked, junk like The Gorge is surprisingly rare.

Slow Horses

[WARNING: I’m going to say less about this show because it’s harder to talk about it without spoiling it, but there are still vague, minor spoilers ahead.]

It’s annoying when Everyone agrees that some piece of Art is excellent and you consume it in the hope that you’ll be able to disagree with Everyone in an interesting way, but you can’t. Slow Horses adapts a series of British spy thrillers about bad British spies—one volume per season, apparently with decreasing fidelity to the original novels as they proceed—and it does so in a way that you might describe as stylish if it weren’t for its Deightonesque seediness.

The supremely seedy Jackson Lamb (Gary Oldman) shepherds a parliament of MI5 rooks-tagged-for-sacrifice2 through their respective professional purgatories, trying to avoid attention from “Second Desk” Diana Taverner (Kristin Scott Thomas), his superior at HQ (“The Park”). We are drip-fed details of Lamb’s own fall from legendary status within the service, while the stories of his subordinates’ career tragedies are lobbed into the proceedings like flashbangs.

Despite, or because of, their failings as spooks, the arc of each season draws these cast-outs into the centre of significant action, where they then make things worse—while we pray they’ll make things better, or at least not die trying.

The nearest the show has to a James Bond is sad-but-gung-ho MI5 nepobaby River Cartwright (Jack Lowden), but it’s the show’s miserable Moneypenny, Catherine Standish (Saskia Reeves) who is the heart of the team. We learn that her backstory is entangled both with Lamb’s and with that of River’s grandfather and former “First Desk”, David Cartwright (Jonathan Pryce).

A lot like the-Slow-Horses-the-protagonists, Slow Horses-the-show combines attention to detail with Not Giving A Shit: The apparently woke plot development that you’re building up a head of outrage about? It’s a red herring, but one we’re going to dangle in front of you until you roll your eyes. That regular character you were warming to? We’re going to kill them in an unpleasant and pointless way.

But, a lot like Jackson Lamb, despite its best efforts, Slow Horses is also cryptically sentimental. Besides its writers’ random cruelty to principals, it tries to hide this sentimentality by being broad: Fart jokes are weak at the best of times, but Lamb’s supposed frequent and noxious emissions are a running gag that’s in need of a hip replacement. This clip is mildly amusing though:

Yes, Slow Horses is sweary and messy and implausible. Yes, multiple characters are deliberately unlikeable (which represents a pleasing extension of Counsell’s Third Heuristic into spy fiction). But it’s also often original and surprising and tense and, fart jokes aside, very funny. Even in its deliberately dated simulation of London, it has sharp things to say about what it’s like to live in the nation’s capital when you aren’t loaded and your life is, literally and metaphorically, hanging by a thread. Like much of the dodgy-men’s-club of gritty-Britty fictional spies that live beyond Bond—Harry Palmer, George Smiley, Joe Lambe [The Game3]—Jackson Lamb and his Slow Horses are even more British than 007.

Aside from being gripping in itself, Slow Horses is a show about one of its the best qualities of many British people: It’s a show about keeping buggering on through dark and dingy times, a show about trying to be a hero even when you’re a zero—and not a Double-Oh.

For All Mankind

[The review covers Seasons One to Three, because, during Season Three—you’ll know the point I mean if you get there—it felt that FAM had turned from a saga into a soap: stuff was happening for the sake of stuff happening, rather than as part of an overarching narrative.]

Until I saw the programme itself, Apple’s promotion of For All Mankind loomed in my peripheral vision like an overtaking tour bus wrapped with the legend: “What If The Space Race, But Women?”

After I’d watched several episodes, I realised that this first impression was not a million miles away from the show’s premise; but it’s a long way to the Moon—a tiny deviation from the true path at the start of your journey, and you’ll miss the target by a light-second4. Yes, FAM is an alternative-history, hard-SF space-race drama starting in the 1960s. Yes, it begins with Soviet Russia landing a man, and then a woman, on the Moon before the US does. Yes, in the FAM timeline, America competes with Russia by deploying its own female astronauts, doing so by reviving the not-alternative-history Mercury 13 programme.

But, after that set-up, FAM develops into something more interesting and less obvious than you’d expect. By that, I mean that it’s about people, not merely identities. People can be fascinating; identities are not.

A show that depicts female astronaut training in the USA from the 1960s can’t avoid speed-running the history of Second-Wave feminism. But, like The Right Stuff, which is explicitly referenced by a minor character at one point, FAM grapples with the history of what we might call modern masculinity without lapsing into psychobabble or platitude. It explores fatherhood as much as motherhood; it establishes a manned presence on parenthood. Indeed, there’s an explosive family scene between major characters in the second season that says deep and true things about being a blood parent and about being an adopted parent. And a passing anecdote about an overweight NASA engineer, a then-minor character, pissing his pants later unlocks a major character’s thoughtful examination of the metaphorical and literal scars of adolescent humiliation. In both cases, men and women drag each other from mutual conflict to shared pain.

Mons veneris, mons pubis, montes lunae

Much as I hate art about identity, there is, however, one “community” that features in For All Mankind that I want to “celebrate” alongside it: homosexuals.

Part of the show’s retro appeal is that it boasts straightforward, 20th-century Women-Who-Love-Women and Men-Who-Love-Men. Because, one quarter into the 21st century, that’s weirdly refreshing, like watching a show about civil rights now we live in the aftermath of the fraud of “Black Lives Matter”. FAM reminds us of a time in which being “out” was career suicide and the idea of any mostly-straight adult finessing ever-so-slightly-divergent-from-the-mean sexual desires into an entire new personality would have seemed grimly hilarious. There’s no “non-binary” this or “queer” that, and the only “transitioning” that looms large in the plot is that from the gravitational influence of the Earth to the gravitational influence of the Moon.

Sappho doesn’t have to be contrived into the drama of Apollo for reasons of “representation”; she’s stage-front because there’s nothing easier to imagine happening when you invite the women of the USA to serve their country in a dangerous and physically demanding setting alongside other women than a U-Haul of lesbians rocking up—except perhaps that, once you’ve recruited a literal army of astronauts, some of them are definitely going to be gay men.

Heterosexuals get a look-in too of course. When their relationships risk cliché, the streaming-service timescale gives the showrunners space to prove their plans for the straights are more subtle—sometimes even hanging a lampshade on an obvious temptation, as they do by explicitly citing The Graduate (twice) as a reference for a fling between a student and the mother of his best friend (though this particular entanglement says more about the enduring effects of a cruelly random childhood bereavement than about mid-20th-century sexual mores). Then there is an exquisite shot of a middle-aged female nerd staring at a middle-aged male nerd’s meaty hand holding an elevator door open that’s worthy of a few paragraphs of Henry James in painting the landscape of their long-suppressed feelings for each other.

The show is honest about society as well as about physics. Of course this generates some counter-intuitive results:

Cute paradox One:

Joel Kinnaman gets star billing—he looks like a star, in the long-limbed, frontier-American mode that goes back to James Stewart and John Wayne, and he can glower with the best of them—but it’s the women who get the most screentime and are the most three-dimensional. As not-quite-first-man-on-the-Moon Ed Baldwin, Kinnaman is meant to depict a frustrated all-American hero; yes, he has to embody the flaws you’d expect from that description; but the female leads—including Wrenn Schmidt, Shantel VanSanten, Krys Marshall, Jodi Balfour, Sarah Jones, Sonya Walger, and Coral Peña—also get to be both heroic-and-likeable and fools-and-jerks.

That’s the final stage of being a “minority” on screen: when you’ve gone beyond token-casting, beyond being allowed to be a villain (again), into a zone of acceptance where you can be portrayed unsympathetically as a matter of routine and portrayed as a rounded human being as a matter of course.

Cute paradox Two:

A series set in the vastness of outer space cares enough about verisimilitude to depict the American(!) living spaces of its principals as relatively small. In the FAM timeline, astronauts are jobbing government employees, who, despite their Corvettes and chunky collectors-piece wristwatches, live in what appear to be, by the standards of the booming eras it depicts, modest circumstances. The production design is both accurate and chic, but it isn’t tempted to dress up reality for the sake of a sexy backdrop.

Cute paradox Three:

The CGI is excellent partly because it has the otherworldly high-contrast crispness that’s going out of fashion in the wider special effects business, but which is true to the way things look outside of Earth’s atmosphere. In the unfiltered, unscattered light of our sun, orbital and lunar vistas resemble oversharpened old-school digital film-making and the sights in them have the no-gravity, no-friction, everything’s-a-point-mass weirdness of the earliest physics engines, which happens to resemble the mechanics of non-falling objects in the vacuum of space.

Rhodes not taken

If you’re not interested in the story-as-a-story, the characters, the effects, or the identity politics5, For All Mankind is full of interesting speculation, as in “speculative fiction”. As the make-up artists put wrinkles on the cast, the screenwriters accumulate wrinkles on the face of their alternative history: In FAM’s timeline, Pope John Paul II is assassinated; John Lennon isn’t; the IRA murder Margaret Thatcher; the Challenger shuttle doesn’t explode; and The Beatles do, eventually, play a reunion concert. For the elected US Presidents in their world, they playfully mix real historic POTUSes with politicians who were losing contenders for the White House in our timeline—until they give us a woman President, but I'm not going to tell you who she is. The real politicians from our timeline are brought to life in theirs with a clever mixture of archive footage, CGI, editing, and some note-perfect impressions by voiceover artists.

Which is neat, because FAM depicts a timeline in which the same energy we directed at digital technology, and content to pour through it, was instead poured into rocket science. This results in another pointed diversion from our reality: In the world of FAM, climate change isn’t believed to be an existential problem because the whole planet committed unapologetically to nuclear fission and then nuclear fusion. Yet its parallel Earth remains a world of struggles. How could it not be? Every drama needs struggles—even a weightless one. This tension made me nod along with a 2022 New York Times review of Season Three:

“All this gives the series something unusual in top-tier TV drama now: an earned sense of optimism. History, “For All Mankind” argues, is not the inevitable product of immutable forces. It is the result of choices. Small choices make bigger choices possible. Early choices (like having women help lead us into space) make later choices imaginable (like having a woman lead the country).”

I’m a sucker both for space opera and for hard-science NASA content and I grew up wanting to be an astronaut as much as the next kid, so I was always going to find something to enjoy in For All Mankind , but I was still surprised at how much it engaged and moved me. As soapy as it eventually becomes, it’s better even than Good Rubbish; it’s great television.

Are you still watching?

Streaming services dread viewers giving up on a show before season’s end or looking away during episodes to doomscroll. But committed Olds like us don’t need preview montages that tell us what’s coming up—thank you Slow Horses—or spicy chapter titles that give the next big story twist away—thank you FAM—to keep us committed; we don’t need to have plot points spelled out to us by the cast to compensate for our trying to watch the smart TV screen and browse the smartphone screen at the same time. Just in case we weren’t watching the thing we clicked “Play” on, the trailer for The Gorge even has a voiceover, seconds in, warning us that the trailer-proper for The Gorge is about to begin!

We Olds do, however, appreciate the extravagance of a retro soundtrack. Heaven knows the sums that Apple spaffed on getting FAM the rights to use Sinatra and Elvis and Nirvana and Marley and the Stones. The show’s official Spotify playlist is packed with bangers. No wonder Apple TV is bleeding hundreds of millions.

[Isn’t Todd Spangler a glorious name?]

I won’t be renewing my Apple TV+ subscription, but if you take one out, one thing you can’t complain about is not being able to see (or hear) where your money is has gone. Apple TV is losing billions because everything they make looks (and sounds) a billion dollars. And everything on it that looks a billion dollars looks that way because it cost millions to make.

Apple TV+ reminds me of Apple hardware back in the 1990s: Even if you were a hardcore nerd who looked down the way the company restricted your access in order to keep things simple for their non-nerd fans, you could only admire the aesthetics, the quality control, and the attention to detail. Apple seemed to make luxury toys for people with more money than savvy, for people with more taste than you. The company’s hardware is now no longer levels-above the competition’s, but its streaming content is elite tier—a luxury for the company as much as it’s a luxury for consumers. How long can sales of Apple’s not-so-elite hardware sustain Apple’s new elite software? I hope long enough to up everyone else’s game.

[If the company doesn’t go bust first, the fifth seasons of both Slow Horses and For All Mankind are due to stream on Apple TV+ in autumn 2025.]

Sorry, cinéastes, movies, like pop songs and popcorn, are meant to be fun. If I wanted a lecture, I’d go to one.

As in the world of John Le Carré, chess pops up in the world of Mick Herron.

This is still available on BBC iPlayer and I recommend it too.

Or you might be there for the hard SF, because FAM opens with a “After the show, learn more about the science behind this episode” screen.