Pod People; odd people; God people; pigs.

How long after the death of satire does allegory have left to live?

[To skip the preamble, scroll down to the heading “Pod People”.]

[SPOILER WARNING]

This substack assumes that you have watched both Invasion Of The Body Snatchers (1956)—or one of its several remakes—and Season One of Pluribus (2025) in full. This isn’t just a nobody-on-the-Internet reviewing B-movie SF content, dammit! This is a Philosophical Treatise! So it’s also one big spoiler.

Though this isn’t a review, I do recommend both Invasion Of The Body Snatchers and Pluribus wholeheartedly, so, if you haven’t watched them already, go away and do so; then come back and read this.

Even though I don’t give much away about it, I’m pretty sure you’ve already read Animal Farm.

tl;dr: History rhymes

In 1954, Halas and Batchelor released a feature-length animated adaptation of George Orwell’s Animal Farm. The original novella was intended as a cautionary (fairy) tale about the the fall of the Russian Revolution into Stalinism; it was also a children’s story played out by anthropomorphic livestock animals, rising up against their human oppressors until their leaders betrayed them. The film replaced the novel’s bleak then-“historically-accurate” ending with an upbeat one. Perhaps because of this change, and because it became a staple of 20th-century western state-school classrooms, most people watching this adaptation didn’t realise that it was itself a anti-communist propaganda film, covertly sponsored by the US Central Intelligence Agency.

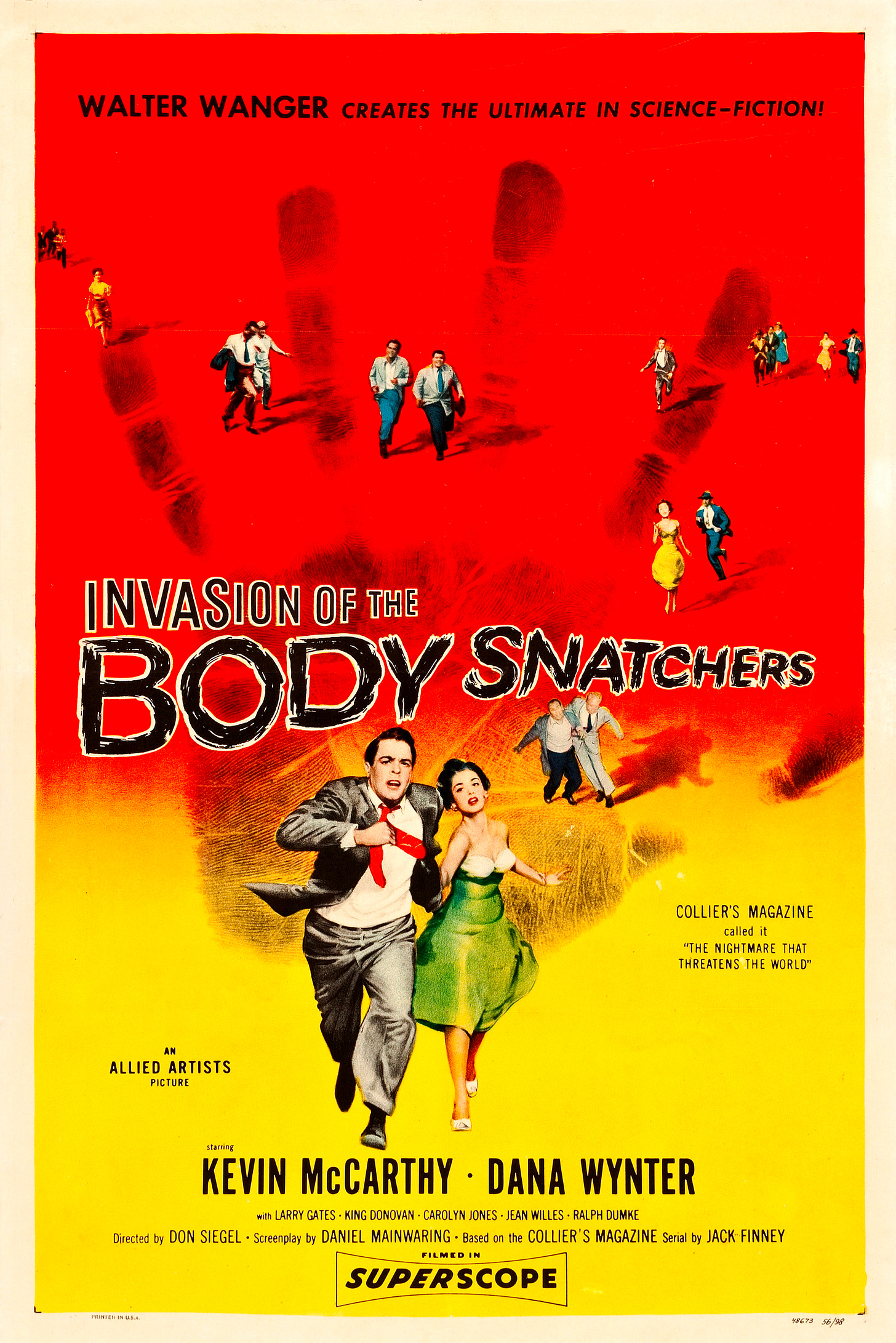

In 1956, Walter Wangler released Don Siegel’s feature-length live-action adaption of Jack Finney’s The Bodysnatchers. After it was shot, it was given both new framing scenes and a more upbeat ending. Most people who’ve seen it assume that it’s about the Red Menace: the real and perceived threat of communist infiltration of mainland America1. But the film’s makers always said that they just wanted to make a profitable B-movie.

In 2025, Angel Studios released a feature-length animated adaptation of George Orwell’s Animal Farm. Despite its shoehorning a fashionable anti-capitalist message into the plot of the anti-communist original, it has not been well reviewed in fashionable media outlets.

In 2025, Apple TV broadcast the first season of Pluribus, a TV show that, by its own admission, is a descendant of Invasion Of The Body Snatchers—though it isn’t another remake to add to the three that followed the 1956 movie, in 1978, 1993, and 2007. Unlike the makers of the 1956 original, I suspect that Pluribus’s makers do want their creation to send several political messages, and that they are wisely coy about those messages.

This post is about what I think the political meanings of Pluribus are. It’s also about the layers of irony that have accumulated on the moving-picture adaptations of Animal Farm andThe Body Snatchers, and about the impossibility of preserving the original intentions of creative works, as culture and technology change around them and critics and audiences fight to co-opt their power.

Pod People

“For me, it started last Thursday.”

Invasion Of The Body Snatchers was made in the United States at a peak of Cold-War paranoia. So it’s apt that two opposing political interpretations of it have been popular with commentators since: Either it was a science fiction thriller whose alien invaders stand in for the hidden communist agents then threatening to take over American society from within and claim it for the expanding totalitarian Soviet empire, or it was a cryptic protest by Left-leaning filmmakers against the insidious threat of anti-communist persecution of creators. We know that both interpretations had a basis in reality: There really were communist agents working to subvert America. Artists, both actual communist traitors and innocents, really did pay a professional price for their politics and their associations.

Neither interpretation excludes a third: that Invasion Of The Body Snatchers, besides being well-crafted, gripping, low-budget entertainment, was a film-noir parable that worked and works because we all know that it’s sometimes true that “They” really are out to get you, that the greatest danger in comfort is that it lulls us into complacency. IotBS’s makers were doomed to channel through their work the dominant currents of their times. Perhaps, the more fantastical and escapist the story you try to tell, the more that story tends to reflect your subconscious preoccupations and those of the people who hear it, the more all of you are prisoners of the reality the story exists in. We all know how our nightmares manifest our anxieties.

What is not ambiguous in the original, even as its script lets the alien spawn of the title pitch their utopian manifesto to the resisting protagonists (and to the audience), is that the body snatchers are the villains. In a film made when extraordinary growth in mass wealth and convenience at home was haunted every day by a forever-war of usually distant and invisible terrors, the bad guys invite the good guys to lay down the wearying burden of eternal vigilance in return for a promise of endless peace.

Pluribus is the latest creation of Vince Gilligan et al.. Gilligan has long been a fan of film noir and a maker of speculative fiction for television. Not only are Pluribus’s in-universe characters aware of Invasion Of The Body Snatchers, they hang a lampshade on the fact. Since the last century, the phrase “Pod People”, derived directly from the original’s plot, has been slang for unthinking (usually political) conformists. Carol, the protagonist of Pluribus, refers to the billions of her fellow humans—who, following The Joining, have become part of a new global Hive Mind—as such in front of The Pod People themselves. But she is living in an actual dystopia/utopia forged by extra-terrestrials; so, unlike pretty much everyone in our universe who’s used the word since the 1950s, she doesn’t do so to insult her political or social enemies metaphorically; she intends the label literally.

Almost everyone important to the making of the original Invasion Of The Body Snatchers insisted that, whatever the intentions of the author of the original novel it adapted, their film didn’t have a political intent. But the B-movie endures as a cultural artefact because the political meanings projected on to it have long since eclipsed its importance as entertainment or art—even as it remains an inspiration to generations of visual storytellers.

We now have three layers of irony:

The original film is almost always referenced in popular discourse, against its creators’ claims, as a political allegory.

In this fictional descendant of the original trope, the original is cited instead, for perhaps the first time in history, as a literal template.

But, unlike the makers of their model, I’m convinced that the creators of this contemporary variant intend their take on IotBS to be very political indeed.

So there is the over-arching cosmic irony that forces beyond film-makers’ control are always going to make audiences see things that were never intended. There is the tragic irony that the particular circumstances that preceded IotBS doomed that to happen: No creator could prevent a film made in the United States of the 1950s, in that tone, with that story, from being interpreted it in a political way. And, today, as viewers, we enjoy the dramatic irony of the protagonist using our metaphor to describe her reality.

Real Space Communism Has Finally Been Tried

Apart from the bigger budget and the newer SFX and the longer running time, Pluribus is a better Body Snatchers because it gives its protagonists better body snatchers—and it gives those body snatchers a better Space Communist Manifesto. Let’s run quickly through the iterations of Pod People Philosophy.

In the original source novel, The Body Snatchers, the human-replacements/copies have all their templates’ memories, but no emotions. Fatally, they are also unable to reproduce. Within years they will die out. When challenged, a pod person justifies his species’ lifecycle to the book’s physician protagonist thusly:

“[W]hat has the human race done except spread over this planet till it swarms the globe several billion strong? What have you done with this very continent but expand till you fill it? And where are the buffalo who roamed this land before you? Gone. Where is the passenger pigeon, which literally darkened the skies of America in flocks of billions? The last one died in a Philadelphia zoo in 1913. Doctor, the function of life is to live if it can, and no other motive can ever be allowed to interfere with that. There is no malice involved; did you hate the buffalo? We must continue because we must; can't you understand that?" He smiled at me pleasantly. "It's the nature of the beast."“

In IotBS, the Reds-Under-The-Beds operated as if Real Communism Had In Fact Been Tried. As in Pluribus, its Space Commies offered a collectivism that needed no coercion, because all live in harmony. Unlike real-world communism, Body-Snatcher communism doesn’t run aground on human nature, because its proles aren’t human—in a perfect implementation of the dreams of communist elites throughout history, it eliminates the original, messy, emotional, intentional people entirely and replaces them with The People, who look the same, have all their memories, but who aren’t people at all. It wants not for liberal crowd-wisdom or free-market co-ordination, because The Hive Mind sees and knows all.

Pluribus’s Keplerite collectivism is even more refined: The People endure as physical individuals, but their brains belong to The Collective. Those whose bodies reject the subjugation of their minds die in the process of conversion. When told of their nearly-one-billion deaths, a stunned Carol replies: “I guess you gotta break a few eggs, huh?”. The long, appalling provenance of that formulation is well-known:

The [New York Times] has a hall proudly displaying its Pulitzer winners. The section devoted to [Walter] Duranty now contains a note which states that his writing about the Ukrainian famine had been tendentious, slovenly and uncritical. This man, who never doubted the legitimacy of the show trials of 1936−1938, often found a way to put a smiley face on a grim country. He wrote that the deaths of all those peasants had been justified by Stalin’s noble purpose, his “march to progress.” Duranty felt that this and other Stalin-era atrocities were nothing to be very concerned about. “If you want to make omelettes,” he paraphrased Robespierre, “you have to break a few eggs.”

This link with communist famine is a neat dovetail with what we later learn about the Keplerites’ food supply.

Putting the genocide to one side for a moment, we have to concede that the Keplerites are bound by a strict moral code. There was no need for them to spread their ideology through violence, because, unless you are immune, one kiss from one of the The Joined is all it takes to recruit you to the cause. It just happens to be true in this story that that recruitment process caused the greatest mass slaughter in the history of the planet. Apart from those “broken eggs”, Pod People cannot deliberately damage even so much as an apple.

We eventually learn that this means that this hardwired constraint puts conventional agriculture outside the reach of The Hive. The Pod People cannot keep livestock, let alone kill it for food. They cannot grow crops to eat, because consumption requires harvesting. A series of accidental observations, of the sort that you might expect from a professional novelist like she is, leads Carol to the chilling truth: that much of the Pod People’s nourishment comes from “HDP”: Human Derived Protein. The Joined are consuming the processed bodies of the frozen dead. This is an echo of what is explicit in the original Body Snatchers novel, and perhaps implied in its offshoots: that the absence of sexual reproduction in human replacements makes their extinction on Earth inevitable.

Even as they are unable to resist the drive to convert everyone on Earth to Join, The Joined cannot “force”2 the remaining immune to become part of The Hive. Indeed, The Joined must do all they can to satisfy the requests of those outside the collective. Their genetic reprogramming also wires The Joined to find happiness in ensuring that The Un-Joined are happy—for some definition of that word.

By steel-manning The Pod Life as non-violent harmony, Pluribus is free to focus on Vince Gilligan’s real interests—and, arguably, the real interests of extended fiction since the emergence of the novel as an art form: character and morality, the human condition beyond the political. But, as the echo of Duranty signals to us, we know from the title of the show itself that Pluribus is also all-in on Big Political Ideas. The reverberations of “E Pluribus Unum”, the legend on the seal of the nation, the unofficial motto of the United States, ring even further down through recorded history—Heraclitus, Augustine, Motteux—and, above all that clamour, the United States Of America has never been a communist country.

Odd people

In Pluribus, there are thirteen human beings whose bodies reject the virus that Joined everyone else still alive on planet Earth3, but who do not die in the process of that rejection—as hundreds of millions of others do. Four of The Immune feature most prominently in the first season. Two are very happy indeed with the happy new world: one nestling in the bosom of her family, the other resting his head on whatever willing bosoms most please him in any moment. But we spend most time with two who both disagree with this new transformed humanity and who were disagreeable individuals in The Beforetimes. Aside from, and originally distant from, Carol, the protagonist, there is Manousos, the grumpy proprietor of a storage facility in Paraguay. (We also briefly meet one other member of The Immune who is unhappy to remain un-Joined, but whom we later witness Joining—about which more later.)

Carol’s motivating backstory is an elegant provocation to a contemporary woke audience: She is a married lesbian who, in the past, had to fight for her identity in a public way; but who, today, remains discreet about her love for women. Her well of antipathy for the urgings of the converted humans surrounding her was filled by her mother’s attempt to “cure” her sexual orientation through “conversion therapy”.

Many contemporary gay and lesbian activists consider “gender affirming care” to be a descendant of such conversion therapy, and believe that it’s used to tell same-sex attracted minors and autistics that they are “the wrong sex”. Many trans activists campaign for laws banning what they believe to be “conversion therapy” are accused of doing so in the hope that such laws will make it impossible for healthcare workers to tell young homosexuals that they are not the wrong sex.

Carol tells her liaison with The Joined , Zosia, that at Carol’s conversion camp, the camp counsellors were “some of the worst people I have ever known. And they smiled all the time, just like you.”

This idea that, once you have changed into a different form from the one in which you were born, you will be happy, that this transformation will free you from feelings of difference or loneliness or suicidal thoughts is so central to the show that it’s embedded into its tagline:

“The most miserable person on Earth must save the World from happiness”

God People

It is one of the most powerful choices of the show that the same Zosia whom Carol repeatedly injures, physically and mentally, with her recklessness and hostility, later seduces Carol, literally and metaphorically. While Carol’s resolve against The Hive is chaotic and fragile, that of Manousos is pure and infinite—because he finds his resolve in God. Manousos believes that The Joined have had their souls stolen; he would rather that they died than that they had to live without them. Alongside Carol’s bleakly ironic “Gotta break a few eggs, huh?”, the unspoken motto of Manousos’s opposition to the Space Commies is “Better Dead Than Red”. We see him endure excruciating physical pain and risk almost-certain death in his quest to defeat the invasion without moral compromise.

Manousos’s objection to space communism isn’t that it prevents humans from enjoying the benefits of free thought or free expression or free markets, but that it steals from humans their God-given freewill. (Gilligan himself was raised a Catholic.) Atop his faith, Manousos’s petit-bourgeois dissent from cosmic collectivism is so hilariously complete that, after The Hive treat him for what would otherwise have been fatal injuries that he suffered on his defiant solo pilgrimage to meet Carol and he can barely stand to leave his care bed, he insists on leaving an IOU to the hospital for the full notional cost of his treatment.

I am being ironically harsh for effect. Yes, Manousos, is a proudly independent small businessman who still believes in property rights, but he leaves IOUs for everyone whose no-longer-property he co-opts on his self-appointed quest “to save the World”. As we discover later, when he makes a harrowing and clumsy attempt to cleave an individual from the collective, we know he does this because he believes that some trace of the original human beings persists somewhere and he hopes that these souls will return to their co-opted bodies. With this return, of course, will come the restoration of the God-given order of consensual free exchange and quotidian suffering.

Anti-Woke Antiheroes

So the two heroes (so far) of Pluribus are a white, North American trad lesbian4, who writes romantasy novels, and a devoutly Catholic South American sole trader, who calls his mother a “bitch” to her face and drives a classic petrol car—a car which, once he’s finished using it, he immolates in the jungle.

Their enemies are permanently blissed-out, vegan, pacifist star-children who conserve energy by sleeping communally and admit they are doomed to starve themselves to extinction because their ideology is incompatible with human biology. They are so anti-human that their collective goal is not the propagation of the species (even in its Joined form), but the propagation of their message across the universe at whatever cost.

It’s also the case that the most materially moral and simply heroic character in Gilligan’s most famous creation was a white, middle-aged, racist cop. With this record, it’s safe to say that the author of this allegory is not going to be standing for office on a Democratic Socialists Of America ticket any time soon.

Message in a bubble

Here are the political messages I take from Pluribus. It’s easy to find reasons to believe that, intentional or not, these messages are there to be taken—because the show’s basic outline is crisp and high-contrast—even if, as you zoom in on its nice details, that shape turns out to be fractal. But I’m not going to pretend that these really are what the show’s makers meant it to say. Worse, I happen to agree with most of these messages.

Like The Body Snatchers, the novel, Pluribus is pro American freedom—in all its painful, grumpy, loneliness. It’s a naughty delight to read a review in The Guardian that—of course!—is uncomfortable with the idea that a current satirical US show could have any other target than the America under Trump:

It takes some chutzpah to look at the world in 2025 – especially if you are a non-Maga citizen of the US – and say to yourself, “Yes, but wouldn’t it be almost more terrible if everybody just … got along?”

Imagine thinking that there could be something more dystopian than living in a free democracy under the Bad Orange Man!

Gen-X-er Gilligan claims that Pluribus does not tell its viewers what to think; he himself invites them to reach their own conclusions about whether or not life would be better as part of The Pod. But, even beyond its side-taking tagline, in its very first episode, it undermines The Pod’s propaganda representative making its central, upbeat offer to the protagonist to “fix her” biological immunity to assimilation with the most sinister musical soundtrack sting we hear in the entire season.

Pluribus is anti-communist and anti-woke. In addition to the explicit textual historical references above, we know Pluribus is anti-communist because the one Pod Person that Carol connects with and tries to disconnect from The Hive, Zosia, is a Pole from Gdańsk, the city whose resistance to communist rule was the domino that ultimately led to the fall of The Wall5. That Zosia not only talks about this time of “opening up” as we’re led to believe she is opening up to Carol, but, when asked for a memory, Zosia recounts a moment of literal and economic consumption (of ice cream) cannot be accidental.

But perhaps the most stark visual evidence for this is the scene that opens the Season One finale: in which Kusimayu, a young Peruvian woman native to a mountain settlement, willingly succumbs to assimilation. We see her life with her apparently loving family in a tourist-postcard traditional village. A refrigerated flask of virus, customized to her genetic make-up, is flown in to this remote location. A serene ceremony accompanied by folk song heralds her convulsive conversion. Smiling beatifically, she walks away with her neighbours, now no longer obliged to play-act for her benefit. The final, telling, shot of this cold open is of the infant goat she cradled lovingly at the start of the scene. Now released by Kusimayu (in accordance with The Hive’s moral programming), it trails behind her, bewildered and abandoned, as she leaves.

This vignette is a masterpiece of horror. It’s both pastoral and serene, yet as hi-tech and terrifying as the infamous “birth” of the monster in Ridley Scott’s Alien. At the instant of assimilation, everything around Kusimayu is exposed as a sham. Since The Joining, she had been living in a Potemkin village, her neighbours’ routines a performance intended to seduce her into joining The Hive—to reassure her that, if she chose the future they offered, she could keep the past she loved.

(The play-acting is identical to that described in the original Body Snatchers novella: alien duplicates perform reassuring theatre for the yet-to-be-converted, but stop their show the moment it becomes redundant.)

As the rest of the episode makes clear, Kusimayu and the people she loved will swap their lives on the land to become drones in the service of The Hive’s ultimate plan: The creation of a gigantic transmitter to forward the message of assimilation. Kusimayu and the villagers will discard Brigadoon for scientific socialism—industrial-scale cannibalism, followed by slow mass starvation, all in pursuit of The Project: to spread an irresistible collectivist biological imperative across the Universe. The crying infant goat is an avatar of Kusimayu’s forsaken love and her people’s cleansing from their homeland.

Commentators have suggested that Pluribus is anti-artificial intelligence. But Gilligan says that—much as he finds the idea appealing and he’s flattered to be thought so prescient—this isn’t the case; he conceived of Pluribus over ten years ago. This puts its birth date near the inflection of the west’s steep ascent to "Peak Woke”. Gilligan’s original concept was of a single man who, overnight, becomes universally adored, and his intention was to explore themes of conformity6.

To me, the aspects of The Joining that don’t resemble communism are the ones that most resemble the conformity of the woke. Kusimayu isn’t a dissident Peruvian peasant targeted for violence by the Shining Path. She experiences no bloody coercion into the dictatorship of the proletariat. Instead, until she Joins, Kusimayu is a victim of benign “cancellation”. Everyone around her shares secrets and solidarity that she cannot—until she surrenders her own distinctiveness to The Hive.

Pluribus is, broadly, anti contemporary trans ideology. Like another speculative fiction Apple TV show named for a famous American motto, it features—it almost celebrates!—old-school homosexuality that chooses not to draw attention to itself, rather than identity-obsessed “queerness”. Its lesbian heroine is afraid of and angry at any threat of her being transformed, “consensually” or otherwise, from the way she was born. Crucially, she is told that her biological conversion into another state would make her happy in way that she cannot understand until she has experienced it—even though her transition to that state would be irreversible.

Pluribus rejects eco-wars and utilitarian declinism. It’s hard to deny this when one of our two heroes gives a painfully on-the-nose rebuke to green politics by telling The Hive where to stick their offers of help as he drives a 1970s petrol-engined car across a continent, parks it in a rainforest, and sets fire to it to stop them from recycling it. In contrast, in every way possible, The Hive has optimised human activity for conservation. Concomitantly, they have made Homo sapiens obligate cannibals and doomed the human race to extinction. Indeed, it’s worse than that: The Hive’s primary goal is to doom countless other races as-yet-unknown to the same fate. Again, it’s difficult to spin this as anything other than a hostile caricature of eco-fascism.

Pluribus identifies the greatest totalitarian threat to human freedom as memetic-genetic, not material. In Pluribus, the Earth is invaded by information: The information begins as a radio signal. Free humans convert the radio signal into a genetic code. The genetic code takes over human beings, not, as in previous body-snatching tales, by changing their bodies, but by changing their minds.

To me, the current real-world ideology that most closely parallels that of The Hive Mind in Pluribus is Islamism. “Islam”’s literal meaning is “submission”. Even if any of the show’s creators had the spread of political Islam in mind when they wrote about The Hive, I doubt this is something that they would even discuss in the writers’ room; it’s certainly something they would never admit in public. But I don’t think it’s an accident—conscious or otherwise—that the one member of The Immune who is hinted to be an active collaborator with The Pod People hails from an Islamic country and responds to The Joining by taking up a literal harem of women.

Once again, the cunning choice to make The Hive disown active violence gives the allegory a stiletto sharpness. What is dangerous about this invasion is not the “invaders” themselves as people; it’s the idea that they carry and that they aim to infect others with. That idea (the Hive virus) literally kills most people who reject it. What hinders the tiny surviving resistance is their reluctance to fight the people carrying the idea. Like communists before them, when they bring their anti-human ideas to liberal states, Islamists exploit this same weakness—and other weaknesses that come with being humane.

“Already it was impossible to say which was which”

My excuse for taking things further than I suspect the message of Pluribus was intended7 is that: There is nothing wrong with getting an allegory “wrong”—in the sense of seeing something in it that its author(s) didn’t plan but haven’t ruled out. Indeed, Gilligan cheekily invites this by telling audiences over and over in interviews to make up their own minds about Pluribus. What is wrong is to invert or distort the content of an allegory in order to claim for it a meaning that it could never have had when intact—or, worse, to steal the valour of an admired allegorical (dissident) work by adapting it in such a way that its intended meaning is inverted, without acknowledging that inversion. It’s wrong like lying is wrong and it’s wrong because it wrongs the artist.

More fundamentally, making a successful claim on the “correct” meaning of an allegorical work, however much it is admired, has as much power in the real world as proving the political affiliation of an imaginary person. The structure of a parable is evidence of nothing more than the literary gifts of its architect. But, when most people agree on the validity of a cautionary tale in itself, there is, of course, much fun to be had from drawing parallels between some aspect of real life of which you disapprove and some aspect of the tale in question.

Allegories and claims about allegories don’t give us factual-historical information about the World, but they do tell us a lot about their authors and their times. If imaginary-world follies help their consumers to recognise real-world follies, then the authors of those imaginary worlds win over real-world minds. Sometimes, all we need to recognise an error is to see it translated into another context. Sometimes, we can become so fixated on a real-world error that we see it in every context.

The same Guardian review of Pluribus I referenced earlier also makes an unintentionally funny effort to spin the show as an allegory of an abusive relationship—funny because the only way it can make this case is by getting wrong almost everything important that happens in the show:

“Pluribus also functions brilliantly as a portrait of (especially) middle-aged womanhood and as an allegory of abusive relationships. Carol is urged to keep her feelings, especially her anger, in check, deny her instincts, reframe her experiences and endlessly believe the best of people – and believe they want the best for her – in the face of mounting evidence to the contrary. She speaks and is not heard. She repeats herself and she is not believed. She shouts and is told to behave better.”

This is such a clear-cut example of straining Guardianista projection that we should be grateful to Gilligan for inspiring it, not least of all because it illuminates what really is so sinister about the show’s enemy: The Hive does not tell Carol to “keep her feelings … in check”; it literally withdraws from Carol to protect itself from the damage (actual death) Carol’s feelings do to its members—in obvious contrast to the behaviour of a real-life abuser. The Hive does not tell Carol to “believe the best of people”; it is scarily open and honest about its motivations and intentions and reassures her repeatedly that she is free to reach her own conclusions about them8. Far from being “not heard” when she speaks, Carol discovers that The Hive will answer every question she asks, and it will do all that it can to meet any spoken request from her—up to and including requests for things that harm The Hive itself. Indeed, a central feature of Manousos’s paranoia is his (justified) fear that The Hive is eavesdropping on his every word via its network of hovering surveillance drones.

The Hive is a threat because it offers the opposite of an abusive relationship: It cannot be violent towards Carol; it cannot coercively control Carol; it is infinitely, unquestioningly attentive to her needs; it will even deny itself the food it needs to live to make her happy. So Carol’s challenge is not to escape her relationship with The Hive—it literally chooses to separate itself from her to protect itself from the violence she has done to it. Her challenge is to find a reason not to Join with it in unholy union when she finds herself falling in love with one of its drones.

Pigs

What if anti-communism, but anti-capitalist?

Just as everybody wants to claim the quoted words of secular saints like Mandela or Gandhi for their cause, everyone wants to claim that a celebrated dystopian fiction is intended to be an allegory attacking their enemies. Sometimes, an allegorical work and its author’s intentions are so explicit and specific that the only way that one-eyed ideologues can wish them otherwise is to remake the allegory in the image of their own ideology. Animal Farm has been so successful and so beloved that generations of communist sympathisers have regarded it with hatred and envy. The original novella is so simple that children can understand and enjoy it—I read it happily before I had any idea what Stalinism was—and George Orwell left no one in doubt of his intentions in writing it and of its referents in the real world. So, of course, it’s the latest victim wilful, tribal, dishonest inversion.

The trailer for this “re-educated” adaptation is enough to convey the scale of the liberties that have been taken with its source material. Even critics sympathetic to its anti-capitalist turn are embarrassed by how completely the Hollywood clique behind the feature has chosen to misunderstand the story it retells:

“Enough of Orwell’s raw material remains for ‘Animal Farm’ to be recognizable — from the dogs Napoleon trains to be his hench-mutts to the slip that sends Boxer to the glue factory — but the film is far too disorderly to substitute for the book. Woe to the student who tries watching this toon instead of doing the reading. To paraphrase Napoleon, when it comes to adapting Orwell: All ‘Animal Farms’ are equal, but some ‘Animal Farms’ are more equal than others.”

This 2025 animated Animal Farm brings us full circle, because, just two years before the original Invasion Of The Body Snatchers, in the same paranoid geopolitical climate, the CIA subsidised the first animated version of Orwell’s novel. The novella was, undeniably, perfect anti-communist propaganda to feed American youth. But not perfect enough for the Office Of Policy Co-ordination. Once again, the ironies compound. The CIA wanted Brits to make the movie, not Americans—because the political Americans couldn’t trust the artistic Americans to complete the mission without subverting it!

And, as with the 1956 Invasion Of The Body Snatchers, the ending of the 1954 Animal Farm was changed to be less dark. In both cases, this seems crazily counterproductive. Surely, the more you want audiences to perceive the bad guys as bad, the worse you want the consequences of their actions to seem?

Shiny Happy People

But this is itself a gloriously, intensely American thing to keep happening when dystopian allegories meet US movie money: What is the Hollywood-shaped American Dream if not the global acme of irrational optimism?9 Animal Farm’s US publishers removed its original subtitle, “A Fairy Story”, when printing the book for the domestic market—before American propagandists made their British agents give their adaptation an inaccurate fairy-tale ending. Decades later, to nearly everyone’s amazement, this fairy story became some kind of truth, because the classically liberal United States of America did, in fact, defeat the communist Soviet Bloc without a hot world war10.

The collectivist title of Pluribus isn’t a quote from The Communist Manifesto; it comes from the Great Seal of the United States of America. The way Pluribus hangs a lampshade on its cannibalism exposition dump is by turning it into a cheery celebrity infomercial, fronted by the co-opted body of a retired American pro-wrestler11!

It’s almost as if it’s impossible for Americans to depict even a cannibalistic global invasion from space, dooming humanity to extinction, without making us smile.

Pluribus imagines a totalitarian ideology that combines economic and political collectivism and eco-declinism with extreme-biotech networked consciousness and nano-targeted feelgood marketing, and suggests that it could wipe out the entire human race without wiping the smile off a single face. Then, as it shows us this happening, it makes us laugh.

Perhaps, despite all my talk of too-on-the-nose anti-communism, that is the ultimate meta-message of the show: That you can sell any horror with a promise of happiness.

For obvious reasons, my linking to Wikipedia’s article on “The Red Menace”, which it titles “Red Scare”, would be worse than pointless.

The inevitable loopholes to this rule are, of course, crucial to the unfolding of the story.

Yes, the virus also infects humans on the International Space Station.

I don’t believe it’s an accident that she wears her hair in a sensible bob and her name sounds a lot like “Karen”. Her surname is a nod to the name of an alien character in a famous episode of The Twilight Zone.

It may also be symbolic that the history of Gdańsk includes periods of conspicuous autonomy from the states in which it was embedded.

Gilligan is being honest here, but he has a record of being politely secretive rather than open—including with his most famous show Breaking Bad. Away from his actual creating, off-set he misdirects audiences to prevent plot leaks and to dodge the controversy that would inevitably follow someone with his high profile being explicit about his intentions. Just like his 1950s Holywood predecessors, he lives in a time when expressing certain opinions has negative career consequences.

600 light years?

Neatly, again, this is something that, when interviewed, Vince Gilligan himself repeatedly says to audiences.

It’s often been claimed that R.E.M.’s Shiny Happy People was built around that phrase appearing on Chinese Communist Party propaganda posters distributed in the aftermath of the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre. Neatly for one of the recurring themes of this essay, its composers deny this.

The cherry-on-the-top of the final episode is Zosia’s delivery of Chekhov’s Atomic Bomb to Carol’s doorstep. Apart from being a funny, clever callback to earlier in the season and a plotting set-up masterstroke, it re-injects the nuclear dread of the original Invasion Of The Body Snatchers into the story after the writers themselves took violence off their table.

Very good. I read despite spoiler warnings - enjoying Pluribus thus far and glad to see that it continues in an interesting trajectory. I actually think in the era of streaming and badly edited, badly plotted, badly scripted movies a spoiler is something that might stop you wasting your time on a series or film that is spun out over interminable false endings and plot contrivances.

What a superb piece of writing! (I ignored your instruction - to watch Pluribus before reading - because of a very old *obsession* with Body Snatchers. It's a film I have actively to prevent myself from watching weekly. I have the memory span of a fruitfly so the "spoilers" won't spoil it for me when I do watch. And like you, I read Animal Farm- and picked up on its warning about collectivism- both before I knew of Stalin, and, I remember distinctly, through my English teacher's stained, gritted and very communist teeth.)